Dancing without AI (Aura Stories 1)

Remembering how to be behaviour analysts when the dashboards go dark

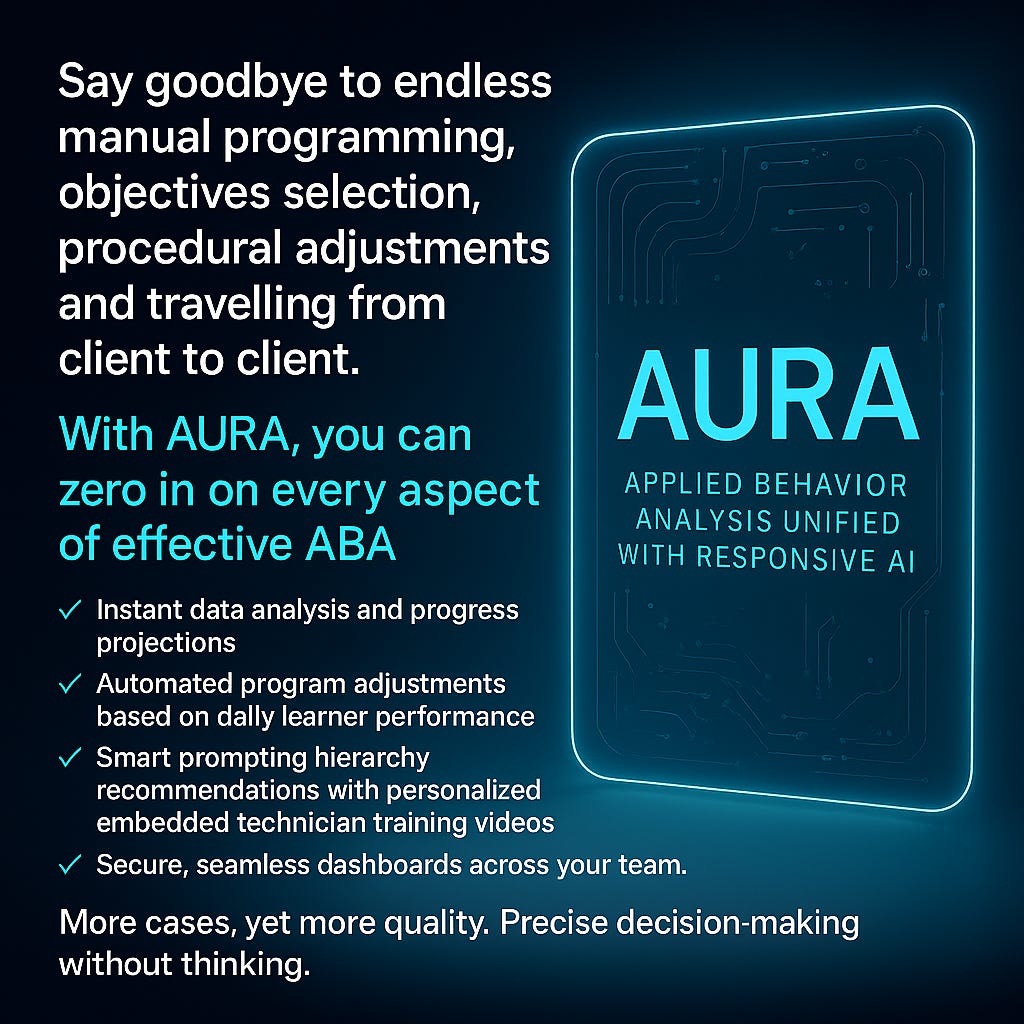

Hello AURA

(Applied Behavior Analysis Unified with Responsive AI)

“AURA, tell me my schedule?” asks Clara, carrying a steaming mug of coffee to her desk.

“Good morning, Clara,” the voice replies warmly. “You have a light day: fifteen clients to review and a CEU webinar on the new AURA data-input update.”

“Thanks, AURA!” Clara smiles. She’s been a consultant behaviour analyst for five years now, and things have changed a lot since she first qualified. With the advent of AI, more children have access to high-quality ABA services, and behaviour analysts have become more efficient. They can handle more cases without losing quality, since they no longer spend hours programming, reading curricular manuals and writing reports. AURA takes care of that.

“Who’s our first child, AURA?”

“Jamie. His data is inconsistent. If you look at yesterday’s graph, he isn’t mastering prepositions. Based on his profile, I projected mastery within four weeks, but the programme needs readjusting or we will not meet this target.”

“Ok, AURA, let’s look at the relevant video segment from the technician’s session.” A video of a technician and Jamie appears on Clara’s screen. She watches the sequence of trials and then asks AURA, “What do you think?”

“The prompts are not coming in fast enough. Jamie makes a response and the prompts come in after the error. We need to reverse the order. I recommend a 0s most-to-least prompting strategy, moving to a 2s prompt delay once independent accurate responding starts. Would you like me to write the exact prompting and fading steps?”

“Do one better, AURA. When the technician logs on for her session notes, run her the relevant training video before she starts teaching prepositions.”

“That’s a great idea, Clara.” Clara nods. “AURA, what’s going on with Sandy?”

AURA explains, “Sandy is currently working on manding for more screen time appropriately. When the technician asks her to release the tablet, she often starts screaming while saying ‘more time, please.’ From the technician’s last session notes, they’ve been using vocal prompting as soon as Sandy is asked to give up the reinforcer. But Sandy is anticipating the interruption and starts screaming ‘no’ as soon as the technician gets up, before she even speaks. When the technician delivers the echoic prompt ‘more time, please,’ Sandy repeats it, while screaming. So, let’s give Sandy a few more degrees of freedom as in more choices in how to communicate her need. She can have a VOCA button that says ‘more time, please,’ and she could also use a card with a picture of the iPad on it. Would you like me to prepare a training video for the technician on how to introduce the additional communication choices?”

Clara nods. “Yes, let’s do that. That sounds like a solid plan.”

Clara switches off her computer. It’s been a productive day. All her clients’ programs have been updated, and the individualised training videos AURA generated are ready for the technician’s next sessions. She takes a deep breath, feeling that familiar sense of efficiency that AURA brings to her daily routine as a behaviour analyst.

“AURA, what do I have tomorrow?” Clara asks.

AURA’s voice replies, “Tomorrow you have a day off to prepare for your trip. I’ve already transferred your clients’ profiles to Theo’s AURA.”

Clara smiles. It’s all seamless. She logs off, knowing that everything is under control.

Leaving AURA behind

Clara packs carefully. Light clothing. It’s going to be hot where she’s headed. She is part of a charity that sponsors behaviour analysts to work in countries just beginning to develop evidence-based autism services. She’s excited. She’s done local charity work before, but this is her first big professional commitment abroad. She’ll be bringing ABA, the science she loves, to those who need it, and training staff to deliver the latest evidence-based strategies. It feels like a calling.

Clara and her four colleagues arrive at their accommodation after a long flight and a bumpy and noisy car ride. The cars look like something out of the movie Grease; at home, they’d be in a museum, but here they’re just everyday vehicles.

The accommodation is spartan but clean, with a vertical fan humming in every room. Clara would kill for an icy Diet Coke, she finds colas in the fridge, but no ice lever, just the perpetual murmur of an old appliance. A knock on the door. It’s Sofia, one of her colleagues, asking if she has any connection. Clara checks her phone: no bars, no signal. They go downstairs to ask their host, Eva, about the Wi-Fi. Eva smiles and says, “Sí, we have Wi-Fi,” then makes a fluttering motion with her hand like a bird. “Sometimes it comes and, sometimes it goes.” Without their devices online there isn’t much to do, no pictures to post on their social media about the incredible experience they are about to embark on. Clara steps out onto the balcony. Even in the city, and despite the loud hum of old engines behind the building, she can hear the sound of the sea, and the accompanying view is stunning: crystal-blue water, white sand, palm trees, and not a neon sign in sight.

That evening the Wi-Fi flickers back to life just long enough for everyone to send WhatsApp messages home: Arrived safely. Long trip. It’s hot here. Wi-Fi a bit unstable, so don’t worry if I go quiet. Then the signal drops again. “I’m sure the centre will have Wi-Fi,” Clara says later, half to Sofia, half to herself. “How else could we do our job?”

The bike ride to the centre is brutal. They set out at seven, while the air is still bearable, but by the time they arrive, sweat is running down their backs and their shirts cling to their skin. That’s why Eva suggested they pack a change of clothes…

The centre’s building itself is striking. High ceilings, heavy wooden shutters, pastel walls with ornate ironwork balconies. It was an old landowner’s villa, which the government has repurposed as a centre for children with developmental disabilities. It has the faded decadence of another time.

Sage, the centre director, is waiting at the door. Her English is perfect, crisp, not a trace of an accent. She explains she moved here twenty years ago, she has family ties, after two decades as both an academic and a clinician abroad. She still travels, attends conferences, and each time she brings back whatever she can: ideas, procedures, toys, flashcards.

Flashcards. Wow, Clara thinks. She hasn’t seen one of those in years. Her kids all use screens.

Learning an old craft

Sage shows them into a staff room lined with books. Some are sun-faded, spines cracked with use. Sage smiles, running her weathered hand along a set of cloth-bound books by B. F. Skinner. “I used to be proud of this collection, they are all first editions,” she says. “But what I’m most proud of now are those.”

She points to the plastic white boxes fixed high on the walls. Air conditioning units. “Now we can have children in all day, rather than just a few hours,” she explains. “Learning.”

On a side table sits a glass display case. Inside, a signed first edition of Verbal Behavior with a note saying “this should be yours forever.” Sage explains she had once sold it, years ago, but when the collector knew why she was giving it up, he told her to keep it and that he would give her the money anyway. The money paid for the first three air conditioners.

Clara knows of the book. She was assigned summaries of the first few chapters, during her online master’s program. She didn’t realise an old book could be so valuable. After a few niceties have been exchanged, Sage, who is not much for superfluous chatter, exclaims:

“Today, I’d like you to observe the staff. Evaluate, write your comments, and we will reconvene at lunchtime to agree on areas that you deem require additional coaching.”

The visitors exchange glances. This is exactly what they had expected to do. Clara, eager to prepare, raises her hand. “Could we have the Wi-Fi password?”

“Of course,” Sage replies with a smile. “But those things won’t work here. We get barely 3G.”

There’s an awkward pause. Clara’s fingers hover over her tablet, suddenly unsure what to do with it. She remembers a reel that went around a few years back of a young woman who asks her grandfather how he was getting on with the tablet she had gifted him, and he says it was great, then proceeds to demonstrate how he uses it as a cutting board. Clara almost laughs out loud. Sage, with the smile of someone who has done this many times before, hands each of them clipboards with a checklist of various items and a ballpoint pen.

Sage leads them through the centre. The classrooms are simple, bright, with some well-loved toys, wooden tables and chairs many-a-time repaired, big washing bowls full of beans and lentils and the soundtrack of sounds of children and teachers at work. Clara notices at once: there are no tablets, no phones. Just staff with clipboards, pencils, and stacks of paper.

One technician is graphing data by hand on lined chart paper, ruler steady, points marked in neat blue ink. Another is running a program with a set of well-worn flashcards. Another is hole-punching a piece of A4 paper to put in a large yellow folder marked “Luca.” A few children watch an old Disney movie on a portable DVD player.

It looks nothing like home. There, everything is streamlined: data gathered on touchpads, graphed instantly, analysed by AURA, and used to guide the next interaction. Here, the materials are scarce, even dated. Yet the staff move with quiet assurance. They observe each movement intently, respond without delay, and adjust one trial after another, without hesitation, without ever glancing at a screen.

Their repertoires live in their eyes, their hands, their voices.

Clara and her colleagues exchange looks, impressed and unsettled. This is ABA, but not the ABA they know. It is ABA in its rawest, truest, form: not on a screen, but in the eyes and hands of people who have learned to see and mould behaviour.

Learning how to dance

For six weeks they, the certified behaviour analysts with their high-level education and titles, will have to learn something new, something that was once taken for granted: how to run a session without a screen, with only their hands, their eyes, their voice and their covert verbal behaviour.

Sofia is already restless, whispering about going home. “Why go through so much trouble for six weeks? At home AURA does it all for us… is it worth it?” But in the end, they all stay, because what they see is simply magical. And when you see something beautiful, you can’t take your eyes off it. More than that, you want to own it.

It is a dance that no AURA can teach you. You can only learn to dance if you move and feel the music. And so they begin to learn this new choreography. As with all first steps, Clara and her colleagues move awkwardly at first, they imitate the staff, but soon they begin to predict the next move, and then they add their flourishes, each bringing something new to the performance.

By the end of the six weeks, Clara and her colleagues can program and run sessions with different learners without once opening a device. If they are unsure, they ask Sage, who sits down with the child, models what to do and then lets them have a go, adjusting their teaching live, moment by moment, shaping their behaviour. Sage’s corrections are sharp, crisp, but clear, never personal. She cuts to the chase. She tells them “well done” when they meet criterion and exactly what to do when they don’t, but she doesn’t lavish them with praise for every step. In the afternoons, they talk about the procedural choices they made and how they relate back to theory.

Sage gives them papers to read. They had not read an actual paper from start to finish in a long time. AURA always breaks it down into manageable units. It’s hard work, but Clara can tact the change in her own verbal behaviour, how she conceptualises a skill, and she is beginning to be able to design a comprehensive individualised without relying on one of Sage’s dog-eared yellowish manual. Sofia asks Sage to remain for a year. But not Clara. On the plane home, she rests her head and closes her eyes and reflects back on her six weeks. Their tablets were silent, their dashboards dark. Yet the children had progressed, and so had they. Without AURA, they had learned how to be behaviour analysts. But Clara wondered how long it would last once she was back in a system that left little room for learning shaped through old-fashioned human interactions. And AURA would be waiting.

Notes from the author

Thank you for reading. You may be wondering if the description of Sage is somewhat autobiographical. In some ways, it is. Sage is the mentor I would like to be. She is a synthesis of several remarkable behaviour analysts I have had the privilege of knowing — Amiris H-R, Valentina B, Veronica B-S, Sara C, Tammy K, Nikia D, Vince C. And I have also been Clara, deeply humbled when meeting behaviour analysts in under-resourced countries who, without technological assistance, have done some of the best teaching I have ever seen. And I have been Sofia too, skeptical and dubious, sometimes looking for an easy way out.

It won’t surprise you that I love dystopian literature, and recently I’ve been exploring AI. As David Cox and Ryan O’Donnell remind us through their excellent Chiron resource, AI is here, and we must be part of the game to shape what it does. We have to become AI literate. My question, perhaps influenced by being able to cite every line of The Matrix verbatim, is: at what cost?

As Morpheus says, “There’s a difference between knowing the path and walking the path.”

Will we lose the skill to tact contingencies in the moment?

Will we lose the skill to change behaviour as it unfolds?

Will we lose the skill to look at a child, interact with them for a little while, and know inductively there and then what and how to teach, without relying on a deductive rule-driven AI objective and procedures generator?

AURA is already here.

AURA is everywhere.

It is all around us.

Not in the name, but soon in all its critical thinking substitution functions. One of many AI “behaviour analyst” interfaces, shaping the way we practise.

A note about the names: Sage is wisdom, the mentor I aspire to be. Clara means clear — the learner beginning to see again. Sofia is wisdom too, but younger, the colleague who stays to keep learning. They are not just characters; they are metaphors for different parts of the behaviour analyst’s journey.

Always impressed by your work and approach to solving problems. Nicely written and an excellent summary of potential pitfalls. I also worry that how behavior analysts are trained exacerbates the problems you outlined. I fear the analysis, understanding of contingencies, and such is getting lost behind procedures and tricks. Thank you for your always thoughtful contributions!

Nice writing, friend! Very poignant. A cautionary tale, for sure